Spaced learning: Why kids benefit from shorter lessons -- with breaks

© 2022 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

opens IMAGE file

opens IMAGE file

What is the "spaced learning" effect? If your child needs to learn something — and you lot want that learning to stick — the best arroyo is to space learning sessions apart in time. A single, long lesson is usually less helpful than multiple, short lessons. A break between studying is a skilful thing!

Information technology's one of the oldest, most reliable findings of cognitive psychology: We tend to learn things improve — embed them more firmly in long-term retentiveness — when we distribute study sessions over time.

But how does this actually work? How long should a written report session be? How much time should laissez passer between sessions?

There isn't any universal, 1-size-fits-all answer. Information technology depends on a student's age, and on what he or she needs to learn. But research offers some rather surprising insights.

For example, suppose you have a young kid who is learning to read. What'south the all-time schedule for honing early literacy skills?

Researchers tackled this question in an experimental study of offset graders (Seabrook et al 2005). They provided all the students with a total of 6 minutes of reading educational activity per 24-hour interval. But each child was assigned to one of two, different schedules:

- Some children received their instruction in a single, six-minute long session.

- Other children received their instruction in three, separate, 2-infinitesimal long sessions, held at different times during the school 24-hour interval.

The researchers tracked the children'southward progress, and administered a reading examination at the written report'south end.

Which kids improved the near? The children who had received the spaced, 2-minute long sessions.

This is just 1 example. It doesn't mean that everybody will do good from learning things in 2-minute bouts. Or that it's ever a adept idea to hold multiple written report sessions in the single day. On the contrary. Different circumstances need different strategies.

For case, if you're an adult trying to learn new words in a foreign language — and yous desire to remember them 12 weeks afterward — experiments advise you should review your words briefly today, and so follow-upward with brusk retrieval sessions on Twenty-four hour period 3, Day 9, and Day 28 (Kang et al 2014).

And then at that place isn't any single schedule that benefits everyone as, in all situations. But there's a relatively simple takeaway, a rule of thumb that most of us can follow. Unless a kid is really focused and enthusiastic most standing a lengthy lesson, it's probably better to break things up.

To encounter what I hateful, consider an experimental study of 1st and 2nd graders, a report that presented kids with a series of brief biological science lessons (Vlach and Sandhofer 2012).

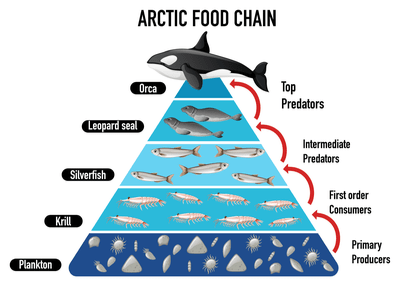

Each lesson was just 5 minutes long, and it followed the same format. The lesson began with an overview of information about food chains – general information that applies to food chains all over the world.

Adjacent, the lesson focused on the details of a food chain in a specific biome, like the Arctic, desert, ocean, grasslands, or swamp. The student learned near five different life forms in the biome, and the role that each life form played in the food chain.

All of the children participated in a total of 4 lessons. But each child was randomly-assigned to 1 of 3 different schedules:

- 12 kids were selected to receive all four lessons on the same day;

- 12 kids were selected to receive 2 lessons on ii sequent days, and

- 12 kids were selected to complete just one lesson per day, for four days in a row.

Each child was tested on his or her knowledge before the study began, and again at the stop – one week after his or her last lesson.

So what happened? How much had children learned?

The children who had received all four lessons in a unmarried twenty-four hours learned about cipher.

Their agreement of food bondage had changed very little. Their exam scores at the end of the study had increased just slightly from their baseline, pre-education scores.

The kids who completed two lessons each twenty-four hour period showed greater growth – an improvement over the kids who'd had to cram all four lessons into i 24-hour interval.

And the biggest gains of all? Those belonged to the kids who had completed just 1 lesson per day. And these kids were peculiarly advanced when information technology came to applying the concepts to novel situations.

For example, they performed much better than other kids on exam questions that asked them to reason near cause and effect in a new, previously unstudied food chain. ("The grass gets sprayed with a poison that makes animals dice when they eat it. What happens to the number of crickets. Does it go upwardly, down, or stay the same?")

Then information technology appears that smaller doses of instruction – spread out over four days – were more than effective than cramming the same corporeality of instruction into just one or 2 days.

Okay…merely this is simply a single, pocket-sized study. What other bear witness is there in favor of the spaced learning effect?

Well, start of all, there'south this: The researchers repeated the food chain experiment on a new gear up of kids, and over again, the "one lesson per day" schedule was linked with the best learning outcomes. Students remembered more, and showed a greater agreement of the concepts (Gluckman et al 2014).

In add-on, experimental studies signal that spaced study sessions are a more effective way for kids to learn multiplication facts (Rea and Modigliani 1985), and retain history facts over the long-term (Carpenter et al 2009).

And for all sorts of verbal information, in that location is ample bear witness for the advantage of spaced practise over "cramming'" Beyond more than than 250 studies, people prove better recall when study sessions are spaced autonomously. A unmarried, lengthy study session is almost never as constructive equally multiple, shorter sessions spread over fourth dimension (Cepeda et al 2006).

The research tells united states something else too. Spaced study sessions are especially successful when they include a testing component.

To see what I hateful, let's go back to the food chain studies.

Those 5-minute lessons weren't merely passive listening sessions. Kids did more than than receive information. They besides had to respond questions well-nigh the material. Questions testing their memory for the facts, and their comprehension of the concepts.

Many studies adjure to the benefits of such testing. Learning is more likely to "stick" when we are forced to search our minds for answers. And information technology appears these benefits are magnified when we combine testing with spaced report sessions (Kang 2016).

More than reading

Looking for more than data about learning and education? These Parenting Science articles might interest you lot:

- opens in a new windowChoosing books for beginning readers: Sometimes less is more than

- opens in a new windowLearning math and scientific discipline: Stimulate deeper processing past asking kids to explain and teach

- opens in a new windowImproving spatial skills in children and teens: 12 evidence-based tips

- opens in a new windowSuddenly homeschooling? Need a curriculum? Here'due south how to get started.

- Pupil-teacher relationships: Why emotional support matters

References: Spaced learning

Carpenter SK, Pashler H and Cepeda NJ. 2009. Using tests to enhance 8th grade students' retention of U.S. history facts. Practical Cognitive Psychology 23: 760-771.

Cepeda NJ, Pashler H, Vul Eastward, Wixted, JT, and Rohrer D. 2006. Distributed practice in verbal call back tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin 132(3), 354.

Cepeda NJ, Vul E, Rohrer D, Wixted JT, Pashler H. 2008. Spacing effects in learning: a temporal ridgeline of optimal retentiveness. Psychol Sci. (eleven):1095-102.

Goossens NA, Camp G, Verkoeijen PP, Tabbers, HK, Bouwmeester S, and Zwaan RA. 2016. Distributed Practice and Retrieval Practice in Primary School Vocabulary Learning: A Multi‐classroom Study. Applied Cognitive Psychology xxx: 700-712.

Kang SH. 2016. Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: Policy implications for instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Encephalon Sciences three: 12-19.

Rea CP and Modigliani Five. 1985. The effect of expanded versus massed practice on the retention of multiplication facts and spelling lists. Human Learning: Journal of Applied Inquiry & Applications 4(1): 11–18.

Rohrer D and Pashler H. 2007. Increasing retention without increasing report time. Current Directions in Psychological Science sixteen(4): 183-186.

Sobel HS, Cepeda NJ, and Kapler IV. 2011. Spacing effects in real-world classroom vocabulary learning. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25: 763–767.

Varga NL, Bauer PJ. 2013. Furnishings of delays on 6-twelvemonth-old children's self-generation and retention of knowledge through integration. J Exp Kid Psychol. 115(2):326-41.

Vlach HA, Sandhofer CM. 2012. Distributing learning over time: the spacing event in children's acquisition and generalization of scientific discipline concepts. Child Dev. 83(4):1137-44.

Title image of girls with microscope by Rawpixel / shutterstock

Image of Arctic food chain past BlueRingMedia / shutterstock

Content of "The spaced learning effect" last modified 10/2020

Source: https://parentingscience.com/spaced-learning/

0 Response to "Spaced learning: Why kids benefit from shorter lessons -- with breaks"

Postar um comentário